Piers Storie-Pugh has travelled to Burma since 1985 and the Chindit Operations is one of his specialities; he has both written and made films about them. He regularly presents his talk “The Chindit Operations of Burma 1943-44”, which is supported by over 150 PowerPoint photographs, many never seen before.

From 1941 disaster followed disaster for Great Britain and her Empire and indeed for the Far East. The fall of Hong Kong on Christmas Day 1941, was followed by the fall of Malaya and the disastrous surrender of Singapore in February 1942. A failed expedition into the Arakan sealed the fate of the Allies at that time.

Field Marshall Wavell sent for Orde Wingate, who had made his name in Palestine and Eritrea and told him to look at the feasibility of long range penetration into Burma. Wingate therefore paid a visit to Mike Calvert, then commanding the Bush Warfare School in Maymyo, right up in the Shan Hills. Together they walked through the jungle discussing the tactics and this was to be the embryo of the Chindits. Wavell decided that all operations into Burma in 1943 should be stood down but Wingate persuaded him that his 3rd LRP Brigade was eager to go ahead. Thus, Operation Longcloth was launched! Commanded personally by Orde Wingate three thousand men and five hundred mules and horses, with air support left Imphal and marched eastwards in February 1943. Along the way they bumped into groups of Japanese, crossed the very fast flowing Chindwin, continued eastwards, cutting railway lines, blowing bridges and perfecting the art of air re-supply lines and met friendly local Burmese. The Japanese were perplexed by both the purpose and how the Chindits were sustained in the field.

Having crossed the Irrawaddy, one of the widest rivers in the world, they were at the extreme range of air supply and becoming boxed in by a swiftly reacting enemy. Imphal Army Headquarters ordered their return to India. Wingate broke up the groups and under their own arrangements headed westwards; some went north via China, others through NE Assam; but some never made it – they had run into the Japanese force, which had gone ahead expecting a follow up Chindit Operation.

Wingate had his enemies not least because Operation Longcloth was expensive in the loss of men and most of those who got back were in no fit state for another such long range expedition.

However, the exploits were given triumphant coverage by the press, eager for some good news and entranced PM Winston Churchill. Wingate was sent for and accompanied the PM to the Quebec Conference. There he shared his vision for future operations, thrilled the American Chiefs of Staff who in any case needed support for their own efforts in China and Wingate gained the promise of sufficient air power to raise five brigades for 1944.

Given this American support it was decided to fly in the Chindits by glider on Operation Thursday, but with Ferguson’s Brigade marching in alone; he did so to protect Stillwell’s right flank advancing from China, south towards Myitkyina.

The most successful Brigade Commander was undoubtedly Brigadier Mike Calvert DSO*. Flown into Broadway with his 3,000 men plus mules and horses, he advanced to Pagoda Hill which dominated the Japanese supply line from Mandalay northwards. He attacked the hill, established White City Fortress and caused havoc in the area. Ferguson, when he arrived after an extremely arduous advance, established Aberdeen; later Jack Masters established Blackpool.

Wingate visited Calvert, and had a wonderful few days meeting officers and soldiers from his old brigade, before flying on to Aberdeen to see Ferguson. Wingate was killed in a plane crash and so in many ways did his dream. However, Mountbatten said that by this time the 14th Army was ‘Chindit minded’.

The Chindits now came under command of the American General Vinegar Joe Stillwell. He hated the ‘Lazy Limies’ but had a huge respect for Wingate.

Without Wingate to protect them and with the gentlemanly Joe Lentaigne as Wingate’s successor, the Chindits were driven ruthlessly hard by Stillwell. He ordered Calvert to head north and capture Mogaung. Described as a mini Passchendaele this battle started on 6th June 1944 (!) and lasted nonstop for three weeks by which time Calvert had only 10% of his force fully fit. Nevertheless, the Chindits captured Mogaung with Chinese support. Suffering from wounds, sores, malaria and other afflictions, not least the demands from Stillwell, they were ordered by Mountbatten to be flown out to India.

The Chindits cut the essential Japanese supply lines to their troops facing Stillwell’s Army: blew up bridges, had fierce hand to hand medieval battles and slowed the Japanese advance towards Kohima and Imphal; causing them to be beleaguered the wrong side of the monsoon. The Chindits lit a flame of hope and did a huge amount to keep the American Chinese Army committed to the front.

Slim’s 14th Army drawn from Great Britain and many parts of the Empire, as well as local troops, may have been the Forgotten Army, but their exploits live on and have become the stuff of legend: The Chindits are right up there in this catalogue of astonishing achievements.

Even in the most atrocious conditions against a cruel enemy, thousands of miles from home, The Chindit Operations will live on in history as endeavours of extraordinary courage, cheek, panache and considerable sacrifice.

Those who were killed on that operation are buried or commemorated in the Htaukkyan War Cemetery or on the Rangoon Memorial. There are over five thousand graves and some twenty thousand names on the memorial – testament to the sacrifice in this Forgotten War.

Some of the Chindits captured were flung in Rangoon Goal and suffered similar dreadful ordeals of cruelty, hunger, beastings, disease and despair as their FEPOW comrades in The Far East.

The infamous Burma-Siam Railway pushed through Three Pagodas Pass, where it crossed the border, to reach Thanbyuziat where one will find the third Commonwealth War Cemetery in Burma.

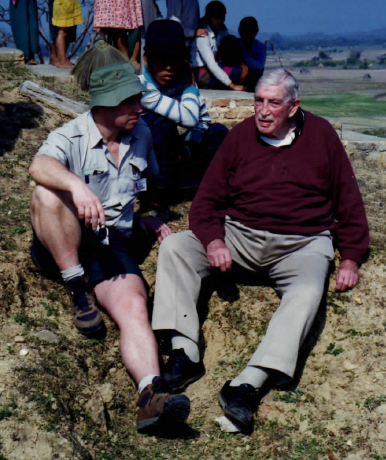

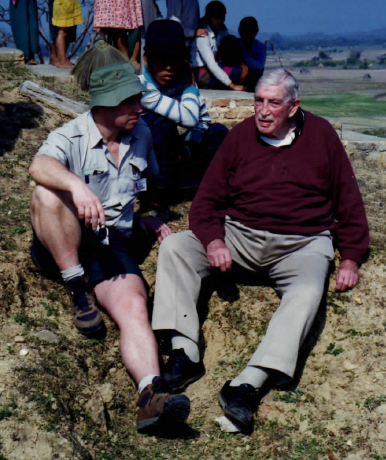

Mike Calvert returned to Burma just once and is seen here with Piers on top of Pagoda Hill which he stormed in March 1944.

For talk or tour enquiries please contact pierss-p@virginmedia.com